The term “personalized learning” is not exactly new; the idea of making each child’s education the best fit for their unique strengths, challenges and interests has long inspired the work of educational innovators. But the Covid pandemic and its dramatic shift to remote learning has made the questions burn even more brightly.

What, exactly, is personalized learning? Why is it so important? What are the best ways to make it work, particularly in schools where a limited number of educators must serve a wide range of learners? And can technology make the job easier, without turning students into screen zombies? Here are at least some of the answers:

Personalized learning sees students not as passive recipients of knowledge, but as active partners in acquiring skills that will serve them not only in school but also in life.

“The current education system was built around teachers being held accountable for their students’ learning instead of the students themselves,” Barbara Bray and Kathleen McClaskey, co-authors of two books on personalized learning, wrote in an article for Government Technology. “This is what most of us learned in school and in teacher education programs, but the approach tends to create a sense of compliancy and ‘learned helplessness’ for both students — the learners — and teachers.”

A healthier approach, they and others say, is for teachers to consider themselves expert guides on journeys students navigate with an increasing sense of their own mastery.

Personalized learning is important because it honors the curiosity burning in every child rather than tamping it down with a one-size-fits-all approach.

Kali Ladd co-founded the Portland, OR, charter school KairosPDX in 2014 with the goal of closing socioeconomic achievement gaps with a deeply personalized approach to each child’s learning. In an interview with Oregon Humanities, Ladd said, “Children are capable of much more than what we often give them credit for, and I think education needs to respect that.”

Student-centered learning emphasizes each child taking charge of their education, having a choice about how to demonstrate their understanding through written or oral expression, and having the chance to lead their peers in group learning activities. Rather than passively receiving and following instructions, they reach for the “why” at every step. “Children are born curious,” Ladd observes. Without personalized, student-driven approaches, many students feel unheard and unmotivated — particularly, she says, students of color. “We actually create educational spaces that crush their curiosity.”

The Covid-19 pandemic has reinforced the value of personalized learning — and made clear that it’s harder for teachers and students working in lower-income communities.

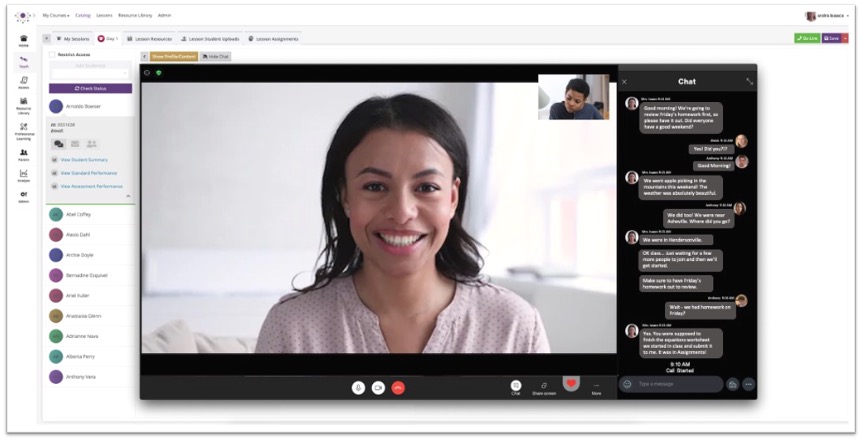

It’s no secret that few students forced to learn at home get much from hours of watching their teachers talk on Zoom. That fact has forced educators not only to get creative in their approach to group instruction but also to individualize the paths of students studying at home. But that’s been tough, particularly in lower-income areas where families lack access to computers and high-speed internet.

“We still have not cracked the nut on how we ensure broadband and device access for all students,” Phyllis Lockett, CEO of the Chicago-based nonprofit LEAP Innovations, told Education Week. “I think one of the silver linings that will come out of the Covid crisis is a movement to make technology access a student right for all learners across America. It is as basic as water and air if we are serious about preparing our students to be competitive in a digital economy.”

While virtual learning has been vital to keeping schools going during the pandemic, it has also pointed up the need for students to get help in developing the self-discipline and other skills needed for success in a remote environment.

According to a recent EdWeek Research Center survey, six in ten educators said students needed more help in managing time, motivating themselves and building the other skills needed for remote schoolwork. And a significant number said students lagged behind in paying attention to virtual lessons, communicating and collaborating.

In an Education Week article exploring those findings, workforce experts said students need those skills not just for their schooling but also for their future workplaces.

“The kids who are able to develop those skills are going to be the leaders of the future,” said Tom Berriman, the principal of Alpena High School in northeastern Michigan. “There’s definitely kids who are developing new skillsets that they absolutely would not have developed pre-COVID.”

Data supports learning — both in-person and remote — by giving teachers and students a way to set realistic goals and measure their progress at every step.

“Our passion for data is based on a belief that behind every number is a story about a (student) trying to fulfill their dream of a high school diploma and a better future,” says Eric Schneider, Chief Academic Officer at Acceleration Academies, a network of dropout re-engagement programs that has led the way in blending remote and in-person learning.

Academy educators keep a close eye on such data points as the amount of time a student spends doing online coursework in a given week, the number of activities they complete within each course, and whether their rate of course completion matches their timetable for earning a diploma.

Schneider’s colleague, Bethel (WA) Acceleration Academy Interim Director Diana Solis, adds: “Ideally, the ability to go big and analyze our progress against national measures of success even as we’re meeting with an individual (student) is to say, ‘Here’s your data story over the past 3 months. How would you like to change that story?’”